The Phantom turned 100 this year. Rolls-Royce chose Goodwood Revival to mark the occasion, not with fanfare or nostalgia, but with presence. Five Phantoms, drawn from across the model’s lifetime, stood together on the Aerodrome Lawn. Each one told its own story of design, of engineering, of the people who ordered them and the world they moved through.

Phantom was never just a car. When Henry Royce introduced the first in 1925, it wasn’t an evolution of the Silver Ghost, but a shift in direction. More refined, more capable, and more adaptable to individual taste, Phantom became the canvas on which clients could project status, style or sentiment. Over eight generations, it remained the company’s flagship and in many ways, its clearest expression of values: silence, effortlessness, longevity, and detail over drama.

At Goodwood, a quiet corner of West Sussex that already carries so much automotive history, the display felt natural. This wasn’t a museum lineup. It was a reminder that craftsmanship, when properly done, holds up.

Here are three of the standouts from the display.

Phantom IV Landaulette

Only 18 Phantom IVs were ever made, and all were reserved for royalty or heads of state. This one still serves the British royal family for ceremonial occasions. The proportions alone set it apart. With a chassis nearly two feet longer than the Silver Wraith and a straight-eight engine under the bonnet, it was built to glide, not rush. The open rear compartment makes sense in its original context. The Landaulette was designed so the public could see its passenger, and in doing so, be reassured by their presence.

The craftsmanship is restrained, formal, and precise. It doesn’t ask for attention, but commands it anyway.

Phantom II Continental Touring by Park Ward

This Phantom II Continental, built on chassis 92PY, sits closer to the opposite end of the spectrum. Originally a private experiment for Henry Royce himself, the Continental version was designed for high-speed touring across Europe’s long, smooth roads. That meant performance took priority, not in the way sports cars chase it, but through weight reduction, wind resistance, and careful engineering.

Commissioned by American industrialist A.Y. Gowen, this example includes a rare sunroof and a yellow-tinted sun visor. It was meant to be used, not hidden away, and it reflects a different kind of luxury. One rooted in movement and function rather than ceremony.

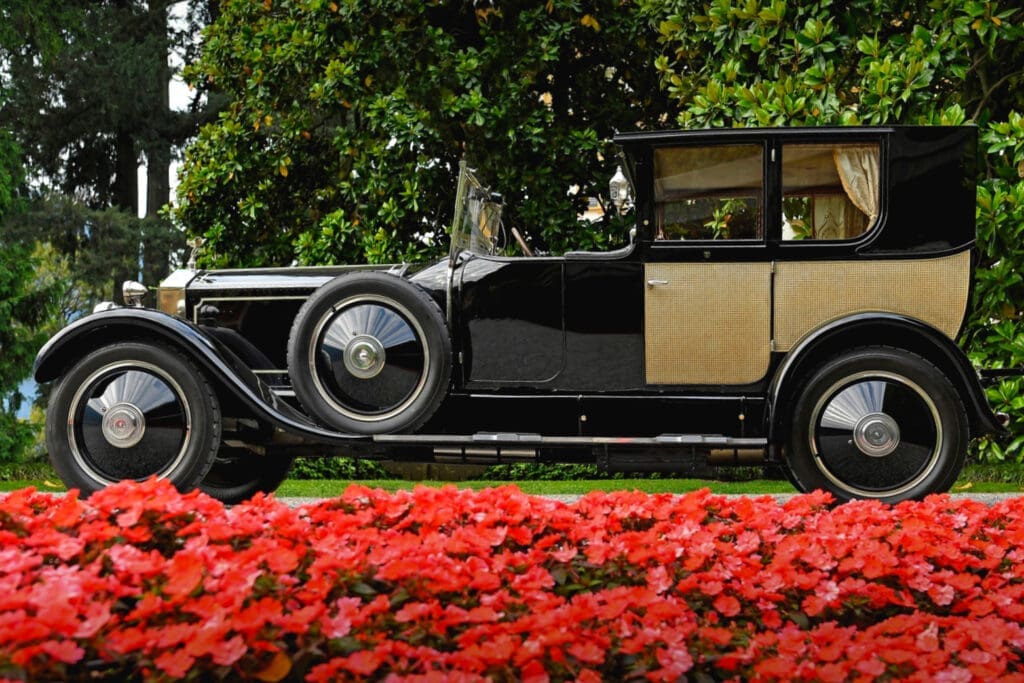

Phantom I Brougham de Ville — ‘The Phantom of Love’

This 1926 Phantom I isn’t subtle. Commissioned by Clarence Gasque as a gift for his wife Maude, an heiress to the Woolworth fortune, the car was built as a tribute to 18th-century French art and interiors. What followed was an almost theatrical level of detail. The cabin features Aubusson tapestries, a painted ceiling with gilded cornices, and a drinks cabinet flanked by porcelain vases and a French ormolu clock.

It’s known today as The Phantom of Love, and that’s not a marketing line. It was a personal gesture, over-the-top and entirely sincere. Whether you find it beautiful or excessive misses the point. It was made for one person, and in that way, it captures what Phantom has always allowed: individuality without compromise.

A Living History

During the Revival, four Phantom course cars ran the circuit between races. It was a small but well-judged touch. These aren’t relics. They’re functioning, road-going records of how people lived and what they valued.

Phantom has never chased trends. It doesn’t need to. When the product is built with patience and purpose, it speaks for itself. That has been true since 1925, and at Goodwood this year, it was clear it still is.

Read about our weekend experience with Rolls-Royce here.