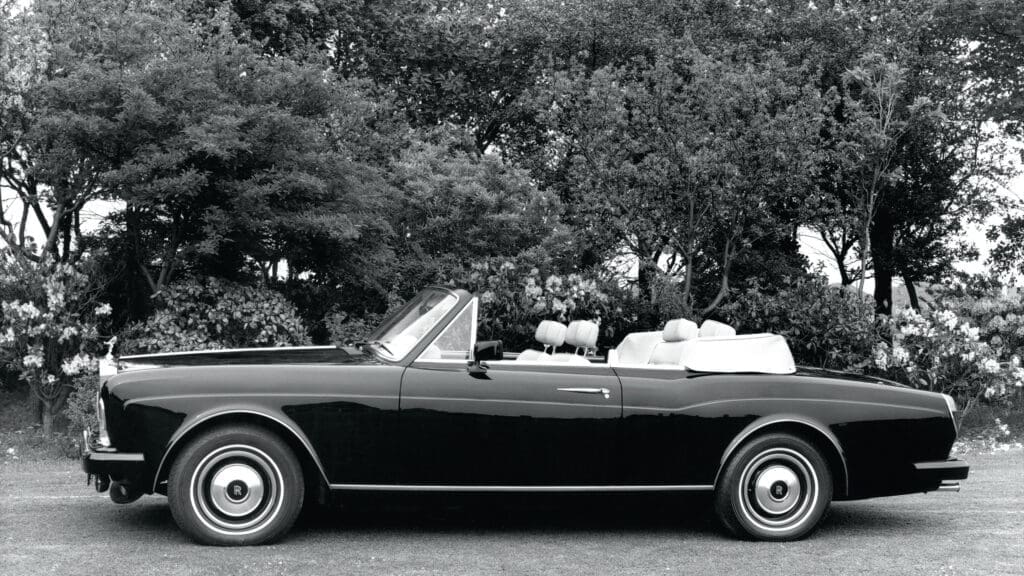

In most lineups, the coupé is the “sporty” derivative. At Rolls-Royce, it is something else entirely: a statement of presence with fewer words. Two doors, a longer sweep of bodywork, and a roofline that looks like it was drawn in one breath. Historically, the coupé has been the format where Rolls-Royce experiments, provokes, and occasionally shocks the traditionalists. That is not a bug. It is the point.

The press-kit language calls it “power, presence and proportion.” Strip out the ceremony and you get the truth: a Rolls-Royce coupé is what people buy when they want the brand’s authority without the formality of a saloon.

The long hood as a cultural signal

Rolls-Royce has always understood that proportion is a kind of social currency. From the early coachbuilt era when clients bought a rolling chassis and commissioned their own two-door body, to the Goodwood cars that brought the coupé back with engineering discipline, the core idea stayed the same. The bonnet is long because it can be. The cabin sits back because it should. The whole thing reads like a tailored jacket with sharp shoulders.

In the Goodwood era, the experimental 100EX and 101EX concepts telegraphed what was coming: shorter, lower, more driver-focused cars that still looked like they could park outside an opera house without asking permission. The boat-tail hints, the “Countryman” style picnic-ready boot idea, even the discreetly reclined grille on 101EX all signaled a brand loosening its tie.

Where theatre became a signature feature

If one detail defines modern Rolls-Royce coupé culture, it is the Starlight Headliner, first seen on 101EX before becoming an icon of the marque. It is equal parts craftsmanship and playful excess, and it changed the way luxury buyers talked about personalization. Not “options,” but atmosphere. Less cockpit, more private lounge.

That matters because Rolls-Royce coupé buyers often want intimacy rather than ceremony. The cabin is still exquisitely made, but the vibe is different. More late-night grand tour than boardroom.

Effortlessness, with a darker edge

Rolls-Royce performance is rarely about numbers for their own sake. Wraith proved you can make a big, heavy luxury coupé feel genuinely urgent without turning it into a caricature. Its Black Badge variants sharpened the brand’s image further, effectively giving Rolls-Royce a sanctioned alter ego for clients who like their luxury with a little mischief.

Then came Spectre, the car that makes the biggest cultural point of all. Rolls-Royce calls it an “ultra-luxury electric super coupé,” and for once the category invention feels justified. Electric drive suits the brand’s long-standing promise of wafting refinement, but it also changes the sensory palette: less mechanical theatre, more near-silent thrust and the faint, expensive hush of well-insulated air.

Who buys a Rolls-Royce coupé and why

These cars are not rational purchases and they are not meant to be. Coupés in this space are declarations: that you travel with intent, that you do not need four doors to prove your importance, and that you value design as much as comfort. They also pull in a slightly younger, more style-led client base, which Wraith and Dawn did particularly well. The polarising bit is obvious too: some buyers still want the traditional grandeur of a saloon. A coupé can read as showy. If that bothers you, you are not the target audience.

The sharpest expression of the brand

Rolls-Royce does “sporty” in its own dialect. The coupé is where the marque feels most distilled: less formal than a Phantom, more expressive than a Ghost, and often more culturally relevant than either. From coachbuilt one-offs like Sweptail to the electric-era statement of Spectre, the message is consistent. In two doors, Rolls-Royce is not trying to fit in. It is trying to be unforgettable.

Read about The Man Behind Rolls-Royce Spirit of Ecstasy here