Three and a half decades after its debut, the final Diablo built reminded two very proper concours that Italian excess still has perfect manners when it counts. Together with others, it turned heads in Italy.

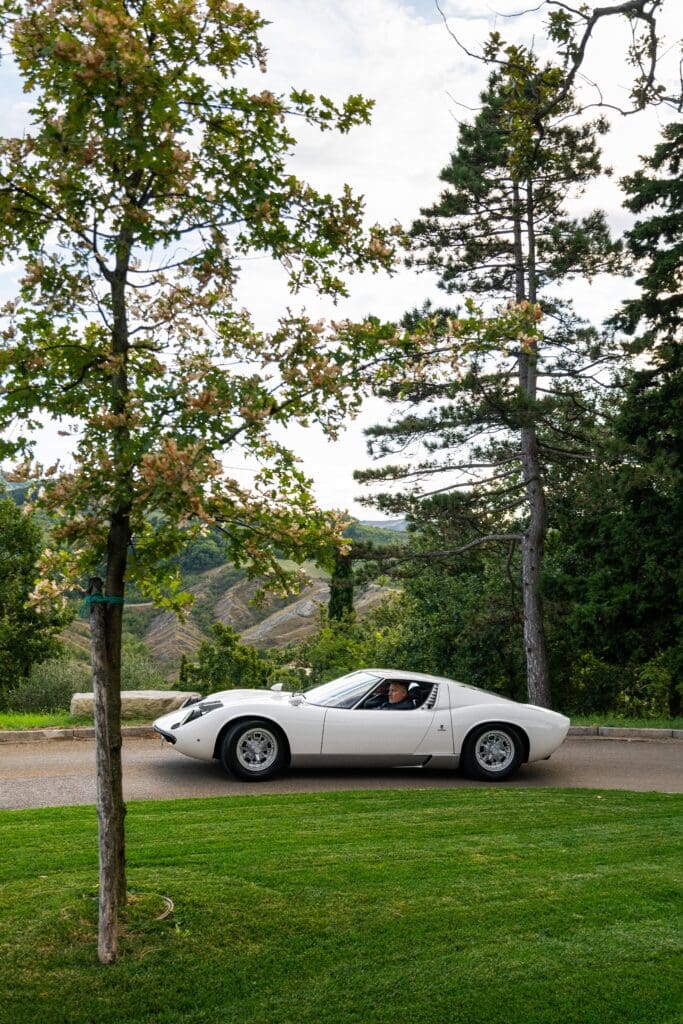

There is a particular thrill when a brand turns its own history into a live performance. Lamborghini did exactly that on two Italian lawns, sending the last-ever Diablo from its collection to the Concorso d’Eleganza Varignana 1705 near Bologna and to the Festival Car in Revigliasco, Moncalieri. It was a birthday lap of honor for the Diablo at 35, and a toast to Polo Storico at 10, the factory department that safeguards Sant’Agata’s past with paperwork, parts and polish. It worked. A Miura P400 certified by Polo Storico took first in the supercar class, a tidy reminder that credibility is as powerful as a V12.

Park a Diablo next to a Miura and a Countach and the family tree reads like a mood board of Italian bravado. The Diablo’s long, low wedge still has that Gandini lineage, all intent and intake. Scissor doors rise like a salute, a gesture that is both theater and function in tight Italian streets. The Miura beside it whispers a different language, a muscular curve rather than a slash, the very shape that made the term supercar stick. Add a 350 GT to the scene, the company’s first production model, and you have Lamborghini’s origin story in metal, progressing from gentlemanly grand tourer to poster-on-the-bedroom-wall.

If modern supercars are curated experiences, the Diablo remains a confession booth. You sit low, the cowhide smells honest, and the glasshouse is shallow enough to make every kilometer feel faster. Sightlines demand attention, the pedal box makes you place your feet with intent, and the switchgear will never be accused of overthinking. That is the charm. There is no intermediary between driver and machine, only the tactile grammar of 1990s Italian ergonomics.

Inside the Lamborghini Countach 5000 QV

Numbers are not the point here, character is. The Diablo’s naturally aspirated V12 idles with a lumpy patience, then climbs toward redline with a rising, metallic clarity that filters through the cabin. The gated manual demands precision, the clutch has a reputation for honesty, and the steering wakes up as the pace builds. It is a car that rewards rhythm more than violence. On the concours lawn it is stationary theater, but everyone present knows its soundtrack, and that knowledge has presence.

Concours events can be peacocks’ parades, yet they are also markets of trust. Polo Storico’s decade of restoration and certification has become a currency, especially for blue-chip Lamborghinis. Judges and collectors want beauty, but they also want proof, and a factory certificate is as good as a handshake from Sant’Agata. The Miura’s class win in Varignana underlines it. Meanwhile, the Festival Car in Moncalieri, listed on the FIVA calendar, gathered proper royalty of the road, an ideal backdrop for a brand that once broke rules and now curates them.

What these gatherings also reveal is a shift in taste. The 1987 Countach 5000 QV from the ASI Bertone Collection still pulls a crowd that grew up on posters, but the 1990s are having a moment. Analog supercars, with their texture and effort, are the new status objects for buyers who want more story than software. A last-of-line Diablo, authenticated and preserved, is a bullseye for that audience.

Lamborghini’s heritage program is learning to speak softly while letting its cars do the shouting. The final Diablo is not just a museum piece, it is a cultural artifact that still feels charged. Pair it with a winning Miura and the origin 350 GT, and you get a narrative arc that is rare in the supercar world, from elegance to audacity to emotion. Two concours, one message. Authenticity matters, and the past can be as exciting as the future when it is this well told.

Read more about cars here.